Managing Winter Temperatures in Naturally Ventilated Dairy Barns

One of the most common issues that occur during the cold-weather months in a naturally ventilated dairy facility is a buildup of humidity that can lead to the creation of condensation on the inside surfaces of your building.

Mature dairy cows generate a great deal of heat, which unfortunately contains a large concentration of moisture from respiration. This becomes troublesome when the condensation collects on the inside surface of your sidewall curtains, freezes into a sheet of ice and prevents your curtain system from operating properly. The added weight of the ice on your curtain fabric can also lead to operating hardware failures, such as cable breakage.

Additionally, when humidity levels rise, so does ammonia, which can degrade air quality.

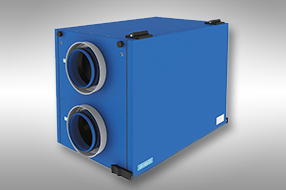

To manage this aspect of the environment, you need to use the part of your natural ventilation system that is designed for cold weather – the ridge ventilation component. This part of your system is designed to remove the warm moist air from the interior during the time of year when your sidewall openings must be restricted due to outside temperatures.

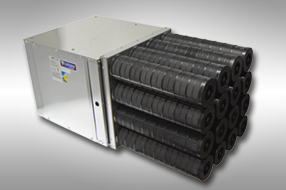

There are three types of ridge ventilation commonly in use: open ridge, overshot ridge and ridge-mounted chimneys. When in the design stage, it is important to make sure that your ridge ventilation is sized properly for the dimensions and capacity of your facility.

If your ridge system has adjustable features (e.g., movable chimney dampers or adjustable curtains on the overshot), only use them to reduce openings when the temperature gets too low and could cause equipment failure or water to freeze in the barn. During the rest of the winter season, leave the ridge openings at full capacity.

The key to operating your natural ventilation system in cold-weather conditions is to maintain a proper interior temperature. We often make the barn too hot, setting the temperature based on our comfort level instead of considering how the cows feel. We have observed that mature cattle do not start increasing their feed intake to replace lost body heat until the temperature is well below freezing. When using natural ventilation to reduce humidity and ammonia, air exchange must be increased in the building. This can be achieved by lowering the temperature, which will allow sidewall curtains to open partially and the ridge system to exhaust at full capacity.

The ideal interior temperature will depend on the construction style of your building, whether it is an insulated or non-insulated structure and how many animals it currently holds compared to its actual capacity. If you are operating your ventilation using a thermostat controller, simply lower the set point on the unit until you achieve proper air quality. If you are running your ventilation manually, a large dial thermometer hung down from the ceiling over a stall area can be extremely helpful. Adjust your curtains using that reading until you reach the desired room temperature. This is a more reliable way to achieve an optimal environment since your adjustments are based on the actual temperature in the area where the cattle are living, rather than how the temperature feels to you.

One simple yet non-scientific method I have used over the years to judge air exchange is when you enter your barn and smell manure before feed, it means the ammonia level and humidity are too high. This suggests that your barn is too warm, and you need to lower the interior temperature to increase the air exchange.

You should aim to keep the barn as cold as possible without creating any mechanical issues. The rule of thumb is, “Cold and dry is better than warm and damp.” To achieve this, you may need to upgrade the quality of your insulated coveralls, but your cattle will be more comfortable, your ventilation system will work better, and your building structure will last longer.

As seen in January 2024 edition of Progressive Dairy Canada.